Alexandria on the Tigris - the forgotten metropolis

In the fourth century BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the Persian Empire of the Achaemenids. "Some of the participants in these campaigns left written reports which give us quite good, sometimes even very detailed information about Alexander's military campaigns", says Stefan Hauser, professor of ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern archaeology at the University of Konstanz. On his return from the Indus region to Mesopotamia, Alexander decided to use the river system to continue from Susa, the Achaemenid capital situated in modern Iran, to Babylon. In this context, he learned that southern Mesopotamia was highly affected by sedimentation, the deposition of fine-grained silt transported down the Babylonian alluvium by both the Tigris and especially the various channels of the slow-moving Euphrates rivers.

As a result, the coastline of the Persian Gulf was constantly pushing outward into the sea, marshes developed, and the traditional harbours were more difficult to reach or even lost their connection to rivers due to changes in their course. According to ancient authors, Alexander decided to establish a new port at a location about 10 stades (2 kilometres) from the Gulf coast at the confluence of the Karun and Tigris rivers. The new city, named Alexandria on the Tigris, thus connected the open sea to inland waterways to the north and east. But how did the city that was later alternatively called Charax Spasinou (“the rampart of Hyspaosines”, a 2nd century ruler) or Charax Maishan (the region’s name) develop in the following centuries? How can people find out more about it today?

© Stefan R HauserMap of Alexandria/Charax

A first inkling

The rediscovery of the city started in the 1960s with John Hansman’s PhD dissertation on changes in the river system between Alexander and the Mongol conquest. Studying aerial photographs by the Royal Air Force, he discovered a site defined by several kilometres of fortification walls. The site's layout and protective walls reminded him of how Pliny the Elder had described Alexandria/Charax in the first century CE. At the time, however, the matter did not go beyond his hypothesis and a brief on-site visit. "The location, known today as Jebel Khayyaber, had traditionally been very difficult to access", Stefan Hauser says. "Aside from Alexandria's heyday being in a period that had long been neglected in historical-archaeological research, the site is only about 15 km from the Iranian border. During the First Gulf War between Iran and Iraq in the 1980s, the region became a major battleground. A military camp was built in the ancient city's ruins."

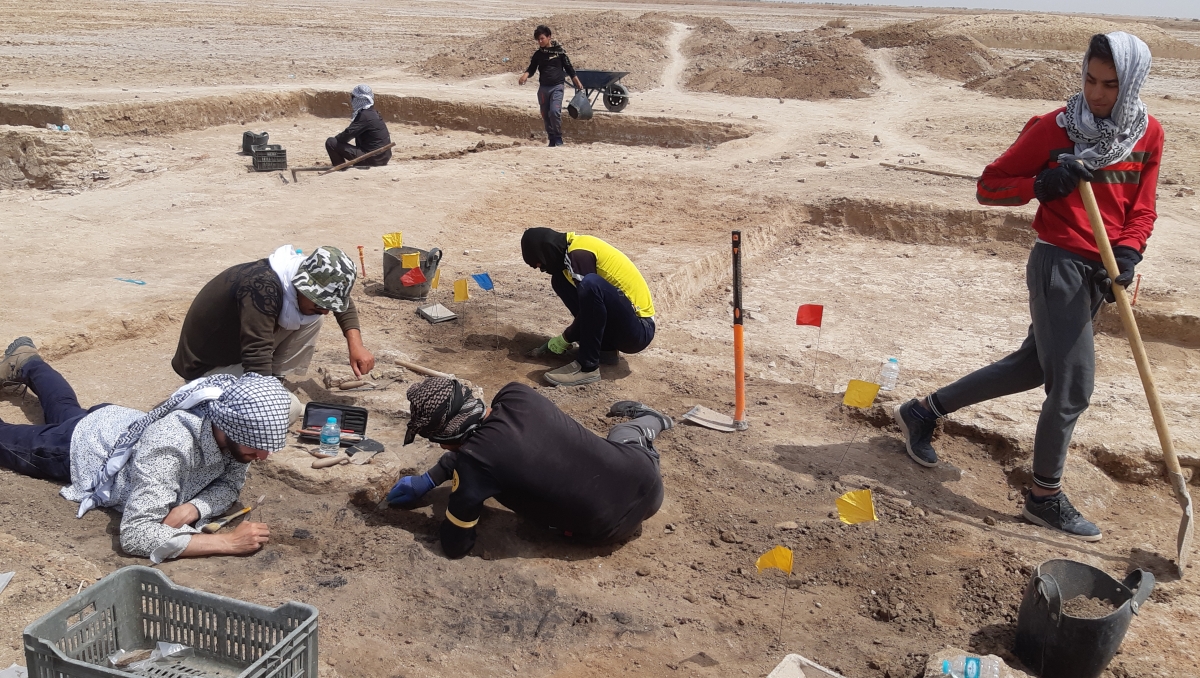

It took until 2013 for a team of British archaeologists, Jane Moon, Robert Killick and Stuart Campbell, to venture an expedition into the region. While they were working near the city of Ur, the director of the Basra Antiquities and Heritage Inspectorate asked whether they would be interested in visiting and possibly working in another place: Jebel Khayabber. The team agreed and drove the 50 km from Basra to the site – bumper to bumper in heavily armoured vehicles, in line with the security protocols then in place. The researchers were very impressed with the mere dimensions of the many kilometres of fortification walls that, even today, still stand up to eight metres tall. On the return trip, they concluded that the huge, but mostly flat ruins were those identified by Hansman as the famous metropolis founded by Alexander. In the spring of 2016, a British team conducted its initial three-week archaeology campaign with stunning results. “Some months later I had the privilege of their generous offer to join the team, since experts on so-called ‘late periods’ in the Near East, i.e. between Alexander and Islam are rare”, says Stefan Hauser.

© Charax Spasinou Project (Stuart Campbell 2017)Just as impressive today: the fortification walls of Alexandria.

Mapping a metropolis

When Hauser first visited the area with his colleagues for the 2017 campaign, the Islamic terror organization that called itself "Islamic State" still controlled large parts of northern Iraq and Syria. Throughout Iraq, the tightest security measures were in place. The archaeologists were only allowed to conduct surface surveys under the close supervision of either soldiers or police officers. "Over the years and organized by Stuart Campbell, we walked across the entire area of Charax and its hinterland to the west, south and east – more than 500 kilometres – and documented all of the surface finds, mainly shards and broken bricks, that provide evidence of past settlement." Using drone images, the team constructed a model of the landscape and recognized: Alexandria on the Tigris was a gigantic metropolis!

© Privat"We realized that we had really found the equivalent of the famous Egyptian city, Alexandria on the Nile. In both places, Alexander the Great founded a city in a location where the open sea meets with rivers, e.g. the inland transport systems. For at least 500 years, Alexandria/Charax served perfectly as a central trade hub."

Stefan Hauser, professor of ancient Mediterranean and Near East archaeology at the University of Konstanz

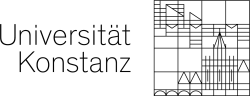

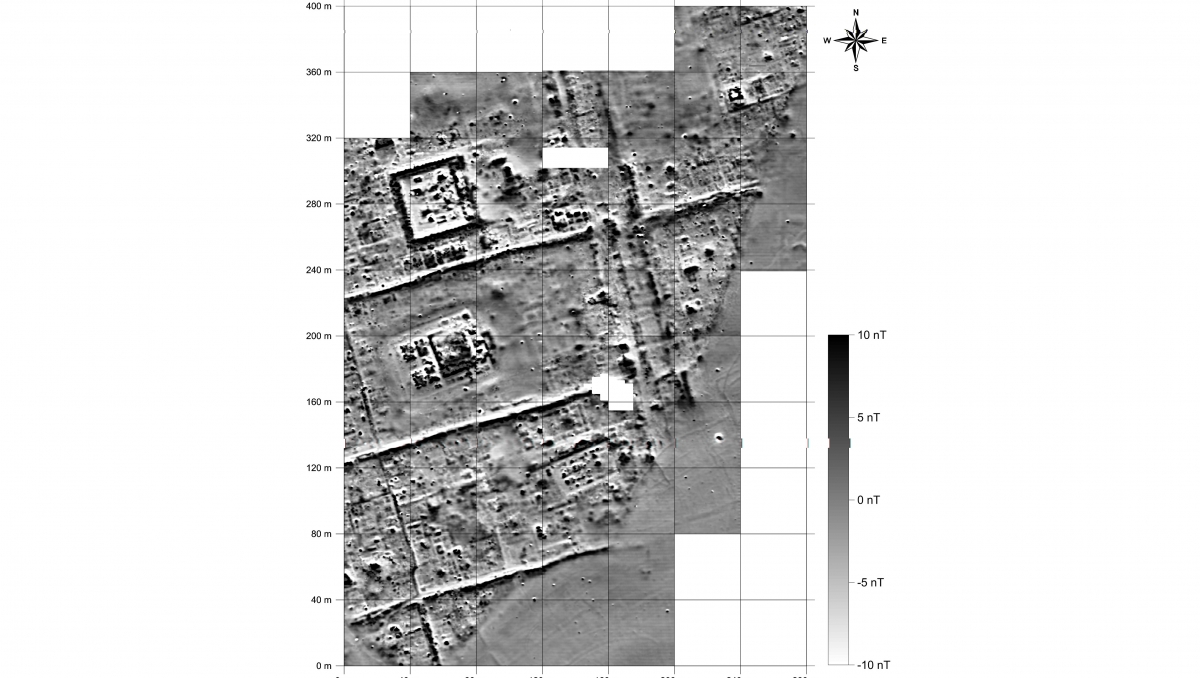

Using geophysics to create a map

The 2016 test campaign involving geophysical prospection confirmed the rich archaeological potential of the site. This non-destructive method is based on the fact that different materials of structures in the ground have minimal but detectable effects on the local magnetic field. Scientists measure these changes (anomalies) in the earth's magnetic field and can assign certain colours to the measured values to produce an image. The Munich-based geophysicist Jörg Faßbinder used a caesium magnetometer, which offers a specifically high resolution, to identify numerous houses and streets in his test area in the city centre. His images immediately demonstrated the site’s importance as they displayed the largest known city blocks from antiquity. In the years that followed, first Campbell and, most recently, Hauser cooperated with the specialized company Eastern Atlas to continue this line of research. The project, which attempts to recreate the entire city plan, is funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

"We quickly recognized that most of the city has a systematic layout. Even two kilometres south of the northern fortification walls we see streets and blocks of houses that are arranged exactly parallel to them. Thus, the city must have been constructed along the lines of a master plan", Hauser concludes. Yet the archaeologist also points to areas which deviate from this grid: "Within the enormous city blocks, we sometimes see building complexes on top of other walls that depart from the grid and were thus likely constructed in a later phase of the city."

Within a total of four different grid orientations in Alexandria/Charax, he reconstructs different construction phases as well as different functional areas. The city had a large residential area which included several large temple complexes. A large number of workshops, including kilns and smelting furnaces were concentrated near an inner-city harbour and canal system. "In another area, we have a palatial complex with no streets nearby. This could indicate that there were parks or vegetable gardens in these locations", Hauser says. In satellite images, the team also identified fields along a dendritic irrigation canal system north of the city.

A perfect location – for a time

During the period between 300 BCE to 300 CE trade intensified between Mesopotamia and India, as well as with Afghanistan and China, and Alexandria/Charax played a pivotal role in this development. To the south of today's Baghdad, two massive cities sprung up on opposite sides of the Tigris, Seleucia and Ctesiphon, that each successively became the capital cities of the Seleucid (starting 312 BCE) and Arsacid Empires (from 141 BCE to 224 CE) respectively. "Evidently, the southern part of the Euphrates turned into marshland. After Alexandria/Charax and, shortly afterwards, Seleucia were founded, the Tigris became the major north-south waterway. During this period, the Euphrates, and thus the former capital city of Babylon which still remained a large city, both decreased in importance", Hauser reconstructs the situation. Capital cities like Seleucia were not only home to powerful rulers and their courts, but also to a large number of inhabitants. Ancient authors from the first and second centuries CE ascribe 400-600,000 residents to Seleucia alone, making it a huge market for goods from India. "Alexander founded Alexandria on the Tigris as a port and distribution centre for trade with India. And all of the goods actually did, apparently, pass through this city. Even after new ports were constructed further to the south, Alexandria was still the location where everything was reloaded for further transport", Hauser explains.

But what happened to the city between this period as a flourishing trade metropolis and the only remaining foundations that stand today? Hauser emphasizes: "Alexandria was dependent on the river in order to serve its intended purpose. However, the Tigris moved further westwards at some, as yet unknown, point in time." To determine the environmental changes that took place around the city, Hauser collaborated with a geologist, who drilled core samples in the area, as well as a specialist in analyzing geophysical data.

"The settlement was probably largely abandoned in the third century CE. By that date, the city was no longer located on the riverfront. The Roman author Pliny writing ca. 65 CE reports that, in his times, due to continued sedimentation, the city which had been founded near the open sea 400 years ago was already 180 kilometres away from the Persian Gulf. Alexandria lost its significance as the capital of the northern Gulf region and as a trade centre, and it was eventually abandoned completely. Its closest successor today is the city of Basra."

Stefan Hauser

Stefan Hauser received funding for the project focusing on Alexandria on the Tigris from the Gerda Henkel Foundation as well as the German Research Foundation (DFG). On the British side, the research was funded by the British Council's Cultural Protection Fund. Additional excavations are planned as soon as the researchers have the funding to do so. Alexandria on the Tigris still has many secrets left to reveal...

Stefan R. Hauser's position as professor of ancient Mediterranean and Near East archaeology is special for a number of reasons. Since 1980 and until just a few years ago, the University of Konstanz was the only German university to include a professorship on the ancient Near East in its history department. At the same time, the department was the first nationwide to explicitly integrate a professorship on archaeology/material culture in the traditionally text-centred field of history.