Physics as a mountain landscape

Imagine standing on top of a mountain. From this vantage point, we can see picturesque valleys and majestic ridges below, and streams wind their way downhill. If a drop of rain falls somewhere on this terrain, gravity guides it along a path until it settles in one of the valleys. The trajectory traced by this droplet is known as a flow line, a path that indicates the direction of movement determined by the landscape’s gradient. The complete network of valleys, ridges, and flow lines forms a topographic (or cartographic) map that captures the organization of the landscape. This organization, which remains stable as long as the terrain does not change, corresponds to a kind of “topological invariant”, as physicists would call it: it characterizes the global structure of the flows without reference to local details.

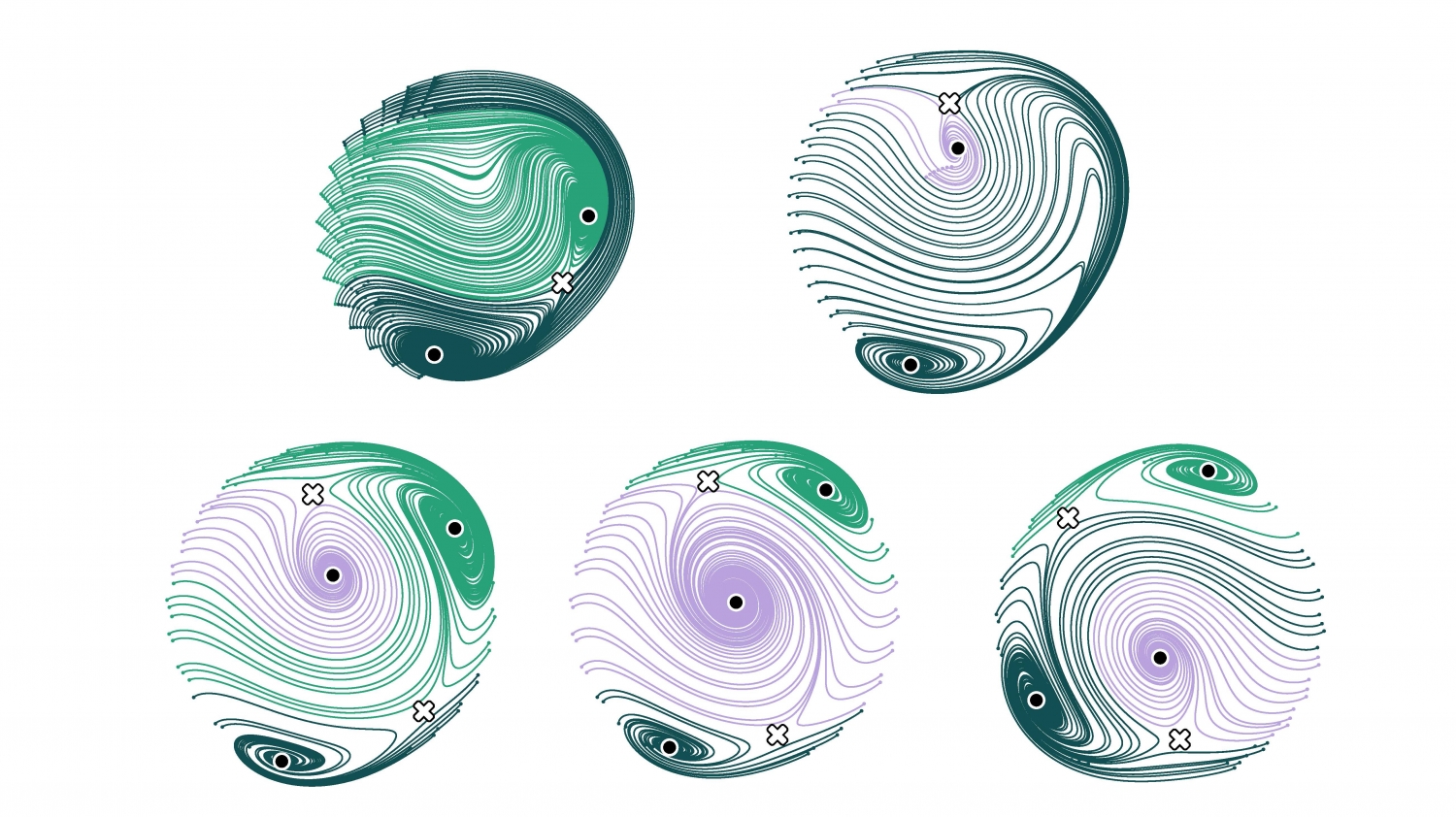

Now imagine that a jolt goes through the landscape and it changes, with new valleys appearing, others merging and ridges shifting. The flow lines reorganize accordingly, forming a new pattern of connections. Comparing these patterns – like two maps placed next to each other – reveals how the system’s topology evolves when its underlying conditions change.

“For us, it is not just about identifying invariants, but about understanding how one stable configuration transforms into another.”

Greta Villa, graduate student in the Zilberberg group

From the mountains to physics and mathematics

What does all this have to do with physics and mathematics? Well, nonlinear physical systems, such as driven-dissipative systems, can be understood in a similar way like our mountain landscape. When systems like MEMS oscillators (micro-electro-mechanical systems) are excited, they exhibit multiple oscillatory states. In our analogy, valleys correspond to stable steady states, ridges to unstable ones, and the streams flowing down the mountain to the system’s evolution toward equilibrium. Phase transitions occur when the landscape itself is reshaped so that valleys and ridges shift, disappear or merge, causing the system’s trajectories to reorganize completely.

In a new publication in Science Advances, a research team from the University of Konstanz, ETH Zurich and CNR INO Trento presents a framework that captures these transformations, providing a unified way to classify and compare them. In this context, the topological invariant defined by the organization of flow lines in the landscape translates directly to the phase organization of resonator systems, where each stable oscillation mode corresponds to a valley in the dynamical landscape.

Topology in physics

The research group led by Oded Zilberberg investigates how a system’s topology, meaning its overall structure and pattern of connections, determines why physical systems can abruptly change their behaviour. Topology, a branch of mathematics that studies properties that remain unchanged under continuous transformations, has become a powerful tool in physics revealing how the global arrangement of a system influences its dynamics.

Traditional topological methods are designed for linear systems. To address the complexity of nonlinear, driven-dissipative systems, the team developed the aforementioned topography-inspired framework that maps the symbolic valleys, ridges and connecting flows of physical systems. In these dynamical systems, however, the flow lines are not elongated streams, but can wind or swirl, showing chirality, a handedness like a screw thread that indicates whether motion winds clockwise or counterclockwise. Including this feature allows for a more complete and precise topological classification of nonlinear behaviour.

© AG Zilberberg, University of KonstanzTopological phase transition in driven-dissipative nonlinear systems. The flow lines show the trajectories that the driven resonator can follow, their landscape, and the chiralities at the attractors, i.e., winding clockwise or counterclockwise.

Abrupt phase transitions

The team’s recent work introduces this framework as a new way to understand how nonlinear systems evolve during phase transitions, that is, during the sudden reorganizations where a system shifts from one stable configuration to another (like the jolt that goes through the mountain landscape and changes it). The key question is what features remain invariant even as the system’s landscape changes. These enduring features, known as topological invariants, provide a global understanding of the system’s structure and stability.

Unlike gradual parameter changes, these transitions happen abruptly. A physical system can remain stable for a long time and then suddenly jump to a new pattern of behaviour. Oded Zilberberg compares this to climbing a ladder: the system does not move smoothly but jumps from one step to the next. The researchers aim to uncover how these jumps occur and how topological invariants connect across transitions. “For us, it is not just about identifying invariants,” says Greta Villa, a graduate student in the Zilberberg group, “but about understanding how one stable configuration transforms into another.”

The analogy of a mountain landscape helps visualize the concept that has highly practical implications.: The results are relevant for photonics, mechanics, electronics and experiments with ultracold atoms near absolute zero. For example, MEMS devices, such as those used in experiments at ETH Zurich by Alexander Eichler’s team, already play key roles in technologies like noise filters in mobile phones, ensuring clear communication even in noisy environments.