Bringing order to nano chaos with centrifugal force

Nanoparticles are so small that they are invisible to the naked eye. If you view them under a special microscope, they look like tiny spheres that can also organize into larger structures. Each particle scatters light and therefore influences energy flow. However, without order in the particle ensemble, the effect remains uncontrollable. Only when acting as a collective nanoparticles reveal their true strength. Researchers are therefore working on methods to bring order to the particles and give them a structure that assigns specific properties to the resulting material. Coatings made of nanoparticles can, for example, make material surfaces especially resistant, generate non-stick or anti-fog properties or cause a targeted reflection of light. If you succeed in influencing the particles precisely, you hold the key to small miracles in your hand.

Colloid chemist Alexander Wittemann and his team at the University of Konstanz's nano lab are working on methods that will make it possible to utilize nanoparticles on a larger scale. As we all know, size is relative. In the world of nanoparticles, it currently means producing a quantity of two grams of similar nanoparticles with a specific shape and symmetry – and doing so as efficiently as possible. What at first sounds like a negligible amount would in fact be unprecedented for nanoparticles of this complexity. Two grams of material contain roughly one hundred trillion nanoparticles – or written out with all the zeros: 100,000,000,000,000. This is, of course, only a very rough estimate, because no one is going to count them individually. Still, it is essential to keep track of them and to sort the particles by size and shape.

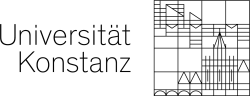

To illustrate this, Alexander Wittemann shows several microscopic images of samples containing nanoparticles. Visible are simple, circular particles. They float in water like little dots or balls, but can also form groups. Using an oil-in-water mixture and ultrasound, the researchers are able to prompt the particles to assemble into well-defined shapes.

"It is a finely tuned interplay between the size of the emulsion droplets and the size of the nanoparticles. Ultrasound makes the oil within the water divide into very fine, evenly distributed droplets. The nanoparticles subsequently accumulate on these droplets. Sometimes only two particles, sometimes three or more. The whole process is similar to building a sandcastle on a beach, where you take a mould to press the grains of sand into a more complex structure, such as a tower. In the case of nanoparticles, the emulsion droplets take on the role of the mould."

Colloid chemist Alexander Wittemann

Once the oil droplets have evaporated, the newly formed particle clusters remain stable. They virtually stick together. The tiny constructs always follow the same rules, so that an identical number of particles invariably form the same kind of assembly – the clusters: Two nanoparticles organize themselves into a kind of dumbbell, four into a small pyramid and seven particles form a flower-like structure. The more particles that come together, the heavier the overall construct becomes. Arranging particle clusters of the same type accurately next to each other results in a material with extraordinary properties. However, this is only possible if you can filter out one specific type, for example, only the pyramid-shaped clusters. But let's not get ahead of ourselves. Currently, we are still looking at a chaos of trillions of particles.

Nanoparticles (here already separated by type) form clusters according to fixed rules. Two particles form little dumbbells (Fig. 2), three particles become triangles (Fig. 3), four emerge as small pyramids (Fig. 4) and so on.

It's a bit like having a huge pile of sand from a gravel pit delivered to your garden. There would be lots of small and larger stones in it and you would have to sort everything out first. Once that work is done, you could spread the fine sand out on the playground, form a pretty border in the garden bed with the small stones, and use the large stones for finally creating the rock garden you've been dreaming of for a long time.

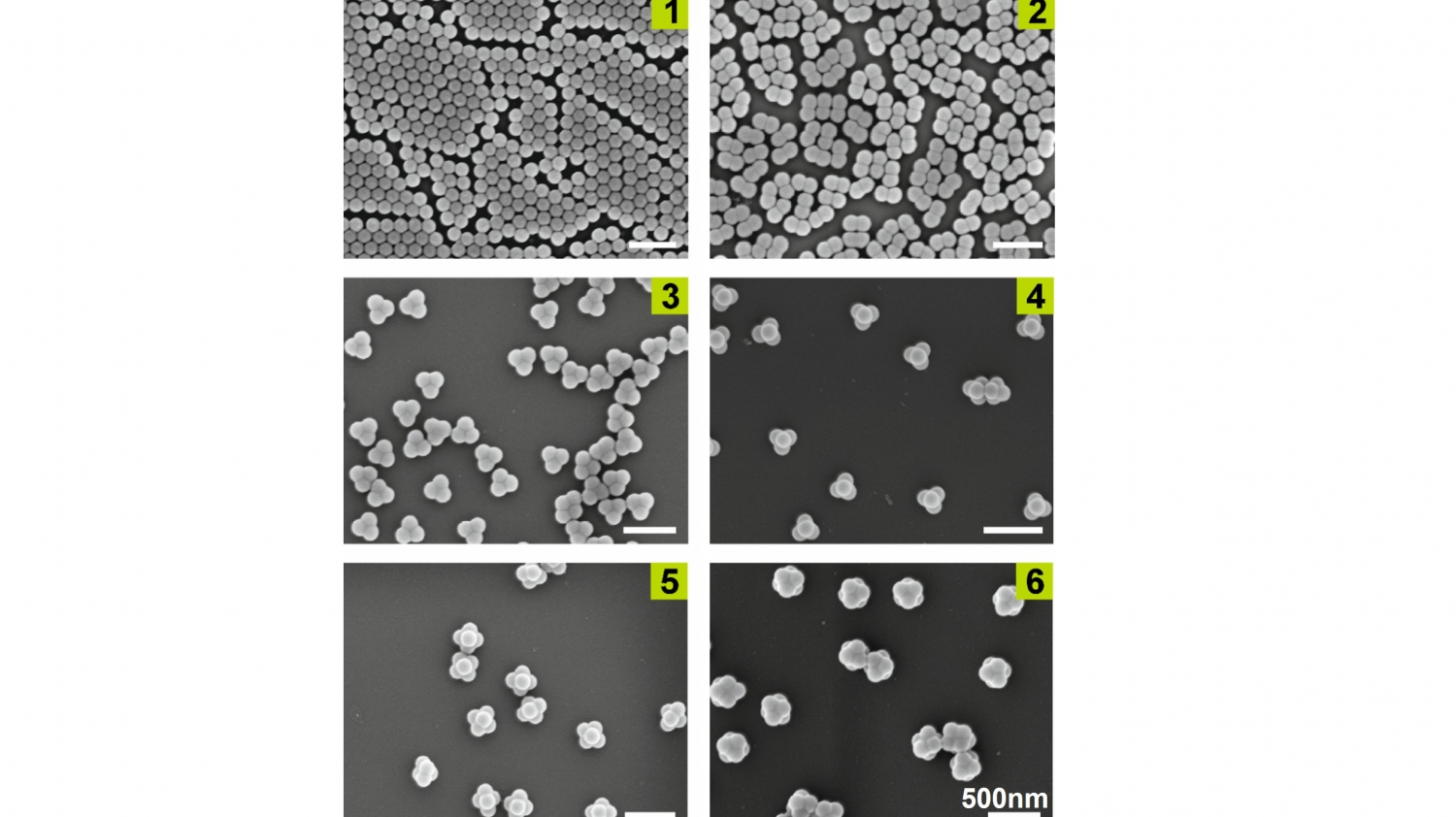

Witteman's rock garden would correspond to a structure of regularly linked, pyramid-shaped clusters of nanoparticles – several trillion of them, in fact. And just as hardly anyone would sort every grain of sand in the pile by hand, Wittemann too uses a kind of physical sieve to separate the particles. The process is not fundamentally new in nanoscience – what's novel is the scale. "Usually, you use small vials for centrifugation, in which liquids with different densities can be layered. Special rotors are needed so that these layers do not mix when the centrifuge starts up and slows down", he explains.

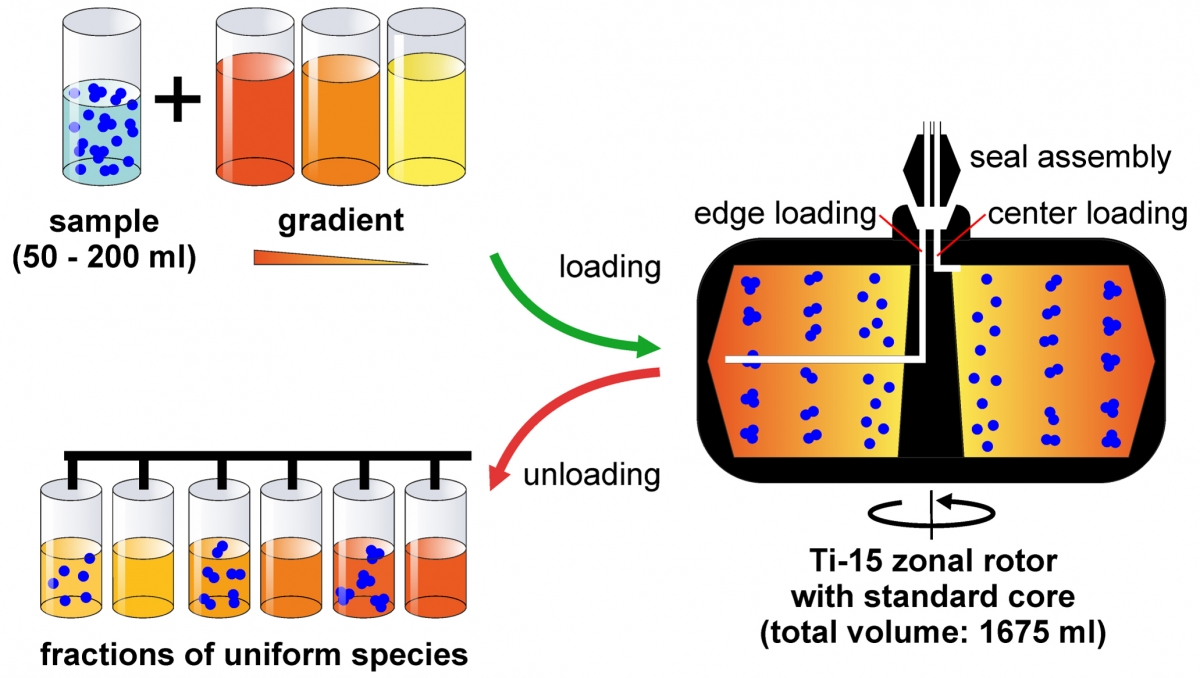

You can imagine this centrifuge like a chain carousel for the vials containing the liquid samples. The vials are inserted and suspended inside the centrifuge, and as the centre axis increasingly rotates, they slowly tilt horizontally, with the centrifugal force holding the chain carousel's passengers firmly in their seats. The same principle is applied in the centrifuge to keep the layers from mixing and to force the nanoparticles toward the bottom of the test tube at a rate determined by their size. The result in the small centrifuge is good, but not particularly efficient. Only a few milligrams of nanoparticles can be obtained per cycle. "But we need much more for actual material production. For any serious testing, we initially set ourselves a target of two grams", says Wittemann.

Results from the nanoparticle studies are described in the following two publications:

Plüisch, C.S.; Bössenecker, B.; Dobler, L.; Wittemann, A. Zonal rotor centrifugation revisited: new horizons in sorting nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 27549. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9RA05140F

Plüisch, C.S.; Stuckert, R.; Wittemann, A. Hybrid nanoparticles separated by buoyant density in a large-scale centrifugal process. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 63, 4488. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.20250248

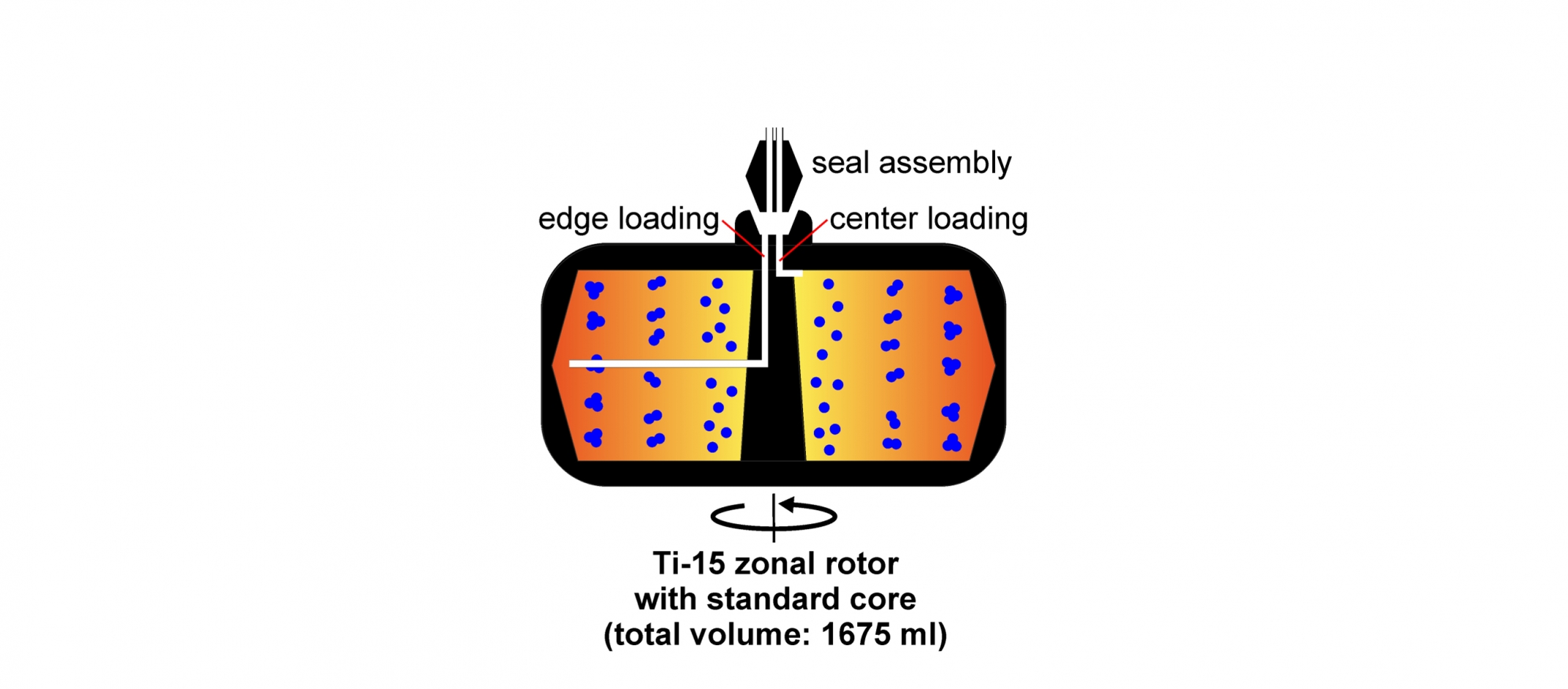

To get closer to that goal, the researcher had to look far beyond his own field. In his search for a centrifuge with the necessary properties and suitable size, the chemist finally found what he was looking for in biology publications. "In the 1960s, centrifuges with special hollow rotors were used on a large scale in vaccine production. Instead of centrifuge vials holding only a few millilitres, these rotors can process as much as 1.7 litres of liquid in a single run. These devices basically offer everything we need today for separating nanoparticles", says Wittemann. However, there was a catch: In vaccine production, this technology had long become obsolete and was replaced by more efficient methods. This made it pretty difficult to find the required rotor. Wittemann finally found what he was looking for at a renowned manufacturer in the US. "It was possible to ship the device, which made us really happy. For the briefing, the very last technician in Europe who still knew how to operate it came by in person. Today he too is retired", says Wittemann. "Fortunately, he brought a younger colleague along for training purposes. That way, the knowledge is not completely lost."

And here the device is now: solid, black and heavy. At first glance, the rotor looks like a medium-sized cooking pot – complete with insert and lid. But the weight of almost twelve kilograms implies that there is more to it than that. The lid is screwed on tightly, the rotor in the centre starts to move and then only two small holes in the lid lead to the centre and edge of the rotor. With a steady hand, a liquid mixture must first be inserted, which is built up in layers: the chemical sieve. Then, the nanoparticles are added. The rotor inside generates enormous centrifugal forces, pressing the particles through the liquid – farther or less far, depending on their size and weight. Light particles remain close to the starting point in the centre of the vessel, while heavier particles are pushed outwards more quickly. It's like shovelling the pile of sand in the garden through sieves of different sizes. In the first one, the large stones get stuck, then the medium and small ones and at the very end the fine sand remains. Except in the centrifuge, the heaviest particles are forced all the way outward, while the lighter ones remain close to the centre. "You end up with vertical fluid layers in which all groups of nanoparticles are neatly separated from each other", explains Wittemann.

Scheme of the separation of nanoparticles in the zonal rotor: The particle mixture (top left) is carefully applied onto sugar solutions, which are layered according to their density. The centrifugal forces in the rotor (right) drive the particles through the individual layers. Larger or heavier particles move faster through the layers of increasing density than smaller or lighter particles. At the end, the different particle types are available as zones of uniform particles, separated according to size or density, and can therefore be selectively extracted (bottom right). [The illustration is taken from the publication: C. S. Plüisch, B. Bössenecker, L. Dobler and A. Wittemann: Zonal rotor centrifugation revisited: new horizons in sorting, RSC Adv., 2019, 9, 27549 DOI: 10.1039/C9RA05140F. It is licensed under CC BY 3.0]In a centrifuge tube, the layering of different particle groups can be easily seen with the naked eye (left). Right: Large-scale separations, on the other hand, are possible in a hollow rotor reminiscent of a cooking pot, which eliminates the need for centrifuge tubes and thus enables the separation of larger quantities of particles. [The illustration is taken from the publication: C. S. Plüisch, B. Bössenecker, L. Dobler and A. Wittemann: Zonal rotor centrifugation revisited: new horizons in sorting, RSC Adv., 2019, 9, 27549 DOI: 10.1039/C9RA05140F. It is licensed under CC BY 3.0]Alexander Wittemann and his team have continuously expanded the experimental setup. Meanwhile, the centrifuge with the rotor is connected to a complex system of hoses, measuring instruments and a sample collector. The goal is to enable the automated separation of complex particle mixtures. Copyright: Simone Plüisch.

While the rotor continues to turn, the particles are removed layer by layer and neatly sorted into test tubes. With these liquids containing uniform sets of nanoparticles, the scientists can later carry out test series for developing new materials. "The centrifuge holds around two litres of liquid, which means we can sort a few grams of nanoparticles per run. Although we are still some way off our target quantity, we are getting closer and closer", says Wittemann. To further optimize the process, he and his research team are working on further automation steps. For example, the liquid is now pumped in and out automatically, and sorting by particle size, too, will soon be fully automated. A larger centrifuge, however, is not an option. "The rotor of this saucepan-size device develops enormous forces, which is why such heavy titanium steel casing is required. If the rotor were to come loose, it could break through walls like a projectile", explains Wittemann. So, for now, the researcher is more than happy to hold off on pushing the limits any further.

Header image: Scheme of the separation of nanoparticles in the zonal rotor

The illustration is taken from the following article:

Zonal rotor centrifugation revisited: new horizons in sorting nanoparticles

C. S. Plüisch, B. Bössenecker, L. Dobler and A. Wittemann, RSC Adv., 2019, 9, 27549 DOI: 10.1039/C9RA05140F